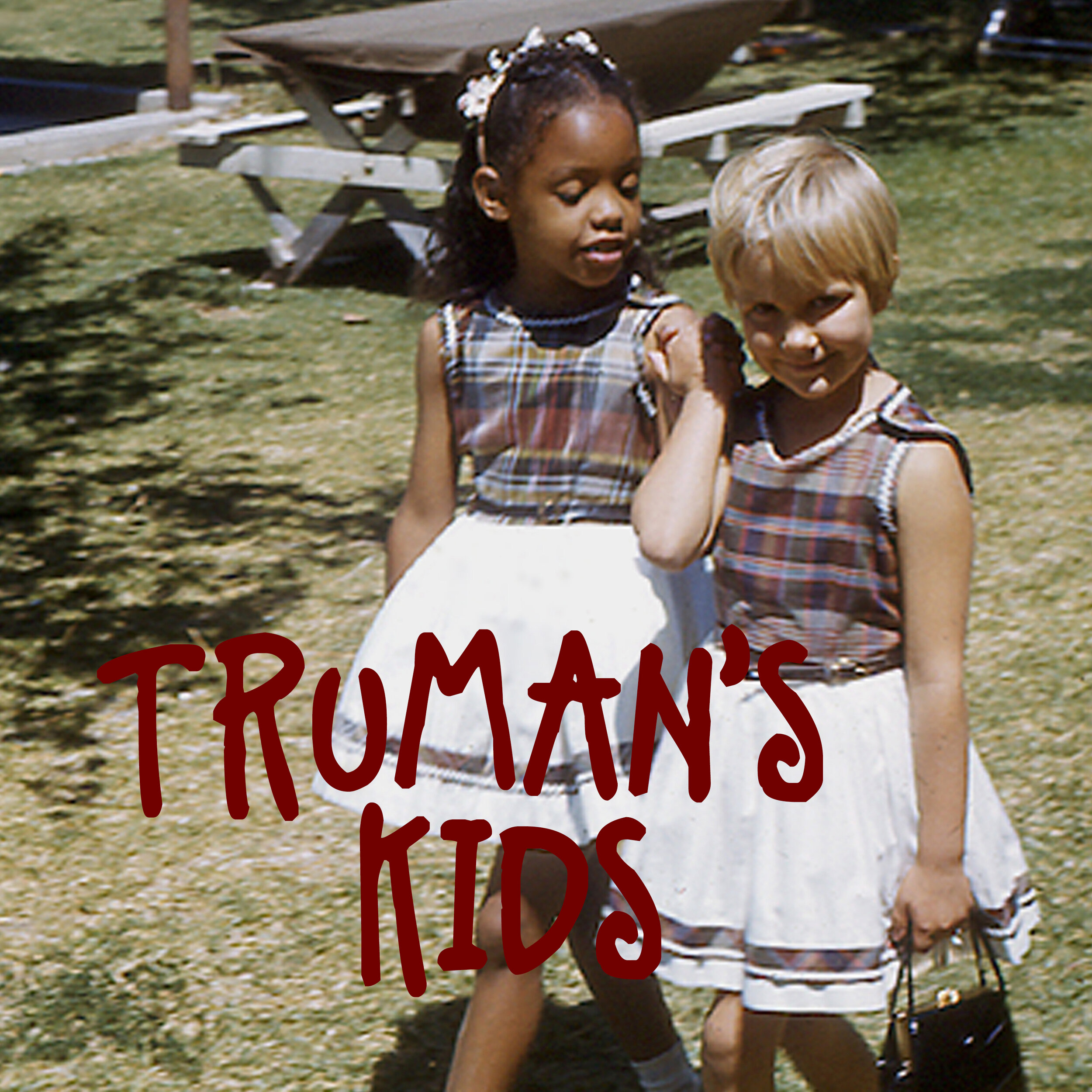

Truman’s Kids

About the film

Air Force Brat Michelle Green and her best friend.

Truman's Kids is a documentary work-in-progress by BRATS filmmaker Donna Musil about the long-term effect of President Truman's 1948 Executive Order integrating the U. S. Armed Forces on military children. Now it doesn't seem like a big deal, but back then, there was strong opposition.

Truman's Kids explores how this "grand experiment" has fared. How living in integrated neighborhood twenty years before the Civil Rights Movement has affected brats over time. How does living outside your country of origin as a child and being exposed to different cultures and religions shape you as an adult? Are brats different from more rooted children when it comes to race and religion? What are their strengths and weaknesses? Can we learn something from this "grand experiment?" Can it be replicated in other contentious areas around the world?

THE DEDICATION - MAJ. GEN. OLIVER DILLARD

Truman's Kids features and is dedicated to Major General Oliver W. Dillard, Sr. (1926-2015), the 5th African-American general in the U.S. Army, who served in both the segregated and integrated armies in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. General Dillard was buried with honors at Arlington Cemetery, overlooking the Pentagon and the Washington Monument. Here are some excerpts from his interview.

THE BACK-STORY

The Outsider. Donna Musil, age 13, skating with her family in Seoul, Korea, 1973.

Race was filmmaker Donna Musil's initial interest in the Military Brat Subculture. A few weeks after finding her old classmates from Taegu (now Daegu) American High School in Korea on the internet through Marc Curtis's Military Brats Registry in 1997, Donna attended an impromptu reunion at a classmate's house in Washington, DC. It was a small get-together. There were only ten students in Donna's 1973 freshman class.

Despite the twenty-year separation, the group instantly bonded. Donna recalls the experience in this excerpt from her chapter in Writing Out of Limbo: International Childhoods, Global Nomads, and Third-Culture Kids, edited by Gene H. Bell-Villada and Nina Sichel:

"I had gone to school in Taegu from 1973 to 1975, around the same time Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge were exacting carnage on their Cambodian countrymen. Not that I was aware of the bloodbath. We had only one television channel—Armed Forces Radio & Television Service—and it broadcast just a couple of hours a day. The only program I remember seeing with any regularity was CBS’s 'Good Times' (1974), a situation comedy starring Esther Rolle and her 'Dy-no-mite' son Jimmy living in a Chicago public housing project. The ten kids in my (entire) ninth-grade class didn’t care about television. We were too busy emulating the soldiers who lived a couple blocks away from our school on Camp Walker. While our parents sipped scotch at the Officers and NCO Clubs, we French-inhaled Kool cigarettes on the golf course to the tunes of Eric Clapton, roamed the fish markets with Parliament Funkadelic, and made out at the Teen Club to David Gates and Bread. We wore our hip-huggers low and our afros high. We sewed peace signs and Black Power fists on our jeans and jackets. It didn’t matter if we were black or white—we were equal opportunity rebels.

Within two weeks of my Internet discovery, I was eating bulgogi, Korean barbecue, and dancing cheek-to-cheek with these older and more subdued revolutionaries, while Al Green crooned 'Let’s Stay Together' (1971) at an impromptu reunion in the Washington, D.C., suburbs. We left the house once in four days, for sustenance, and barely slept. The more we talked, the more I realized that while we physically looked like Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition, our experiences, insecurities, even our accents, were like the cookie-cutter houses in which we had grown up. I finally 'fit.' I had 'people!' I knew where I was 'from.' I wanted to snuggle up inside that warm cocoon and never leave.

Life goes on, of course, and even as we hugged and cried and promised to stay in touch, most of us didn’t. Still, it made a difference, knowing there were people in this world who knew me as a girl and accepted me as a woman, with all of my peculiarities and peccadilloes. I also couldn’t shake the feeling that the weekend was somehow significant beyond me and my friends. If Taegu American High School was any indication, Truman’s Grand Experiment was a resounding success and military brats were a living study in race relations. When I searched the Internet, however, there was no scientific study, no editorial opinion, no mention at all of how President Harry Truman’s Executive Order integrating the military in 1948 had affected its smallest and youngest research participants. I decided to explore the topic myself, to make a documentary about race relations and military children. I hadn’t picked up a camera professionally since college, but I was never one to let a little thing like practicality get in the way.

participate!

If you're interested in participating in the documentary, Truman's Kids, by donating stories, photographs, or footage, please fill out our Mailing List and we will send you more information. (Please do not send us your original photographs or footage in the mail!)

If you would like to support the documentary by making a tax-exempt donation, please go to our Donation Page and follow the instructions.